Approaching the Cretan Diet in Today’s Times

- The first study of the “Mediterranean dietary pattern” (MDP) took place in 1948. The Greek government, which was working to improve the conditions of its population after World War II, invited the Rockefeller Foundation to conduct an epidemiological study on the island of Crete. Thus, epidemiologist Leland Allbaugh conducted a comprehensive survey of the demographic, social, economic and nutritional characteristics of the population.

- [Nestle M. Mediterranean diets: historical and research overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995; 61 (6 Suppl): 1313S–2].

- The results showed that at least 61% of the total energy in the Cretan diet came from plant foods, such as cereals, legumes, fruits and vegetables. Only 7% of calories came from animal foods such as meat, fish, eggs and dairy products.

- In contrast, the food supply in the US at that time contributed only 37% of the energy from plant foods.

- [Nestle M. Mediterranean diets: historical and research overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995; 61 (6 Suppl): 1313S–2].

- “…olives, cereal grains, pulses, fruit, wild greens and herbs, together with limited quantities of goat meat and milk, game, and fish consist the basic Cretan foods…no meal was complete without bread….. Olives and olive oil contributed heavily to the energy intake … food seemed literally to be ‘swimming’ in oil“.

- [Crete: A Case Study of an Underdeveloped Area”, L. G. Allbaugh, Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1953].

- The researchers observed few nutritional problems in Crete. However, some study participants expressed dissatisfaction with their diet, citing meat as a food that was missing from their diet, a “diet of necessity.” Allbaugh noted that the Cretan diet could be improved by incorporating more animal-based foods.

- [Nestle M. Mediterranean diets: historical and research overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995; 61 (6 Suppl): 1313S–2].

- In 1952, Ancel Keys initiated the Seven Countries Study to examine the relationship between diet and health in Italy, Greece, the United States, Japan, Finland, the Netherlands, and Yugoslavia. This study, which lasted nearly three decades and included approximately 12,000 men aged 40-59, was one of the first to link the Mediterranean dietary pattern to health.

- [Keys AE. Seven countries: a multivariate analysis of death and coronary heart disease. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1980].

- The results showed strong evidence linking dietary intake with serum cholesterol levels and cardiovascular disease, while lower rates of cardiovascular disease were observed among participants with low saturated fat consumption.

- [Nestle M. Mediterranean diets: historical and research overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995; 61 (6 Suppl): 1313S–2].

- [Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P. Healthy traditional Mediterranean diet: an expression of culture, history, and lifestyle. Nutr Rev. 1997; 55 (11 Pt 1): 383–9].

- The Cretan diet derived about 38% of calories from fat, similar to the proportion in foods in the United States. However, in Crete, table fat came mainly from plant-based foods such as olives and olive oil. Keys noted that Crete had a rate of coronary heart disease (CHD) almost 32 times lower than Eastern Finland, although total fat intake in Crete was not much lower (36.1% of total energy intake and 38.5%, respectively). However, saturated fatty acids (SFA) contributed 23.7% of total calories in Eastern Finland, compared to 7.7% in Crete, a major reason for the low cardiovascular events recorded in Crete, Keys concluded.

- [Keys AE. Seven countries: a multivariate analysis of death and coronary heart disease. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1980].

- The inspired French medical researcher, Serge Renaud, always using the term “Cretan-Mediterranean diet” wrote: We conclude that the Cretan Mediterranean diet adapted to a Western population protects against coronary heart disease much more effectively than a prudent diet. The favorable life expectancy of Cretans could be largely due to their diet.

- [Renaud S, de Lorgeril M, Delaye J, Guidollet J, Jacquard F, Mamelle N, Martin JL, Monjaud I, Salen P, Toubol P. Cretan Mediterranean diet for prevention of coronary heart disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995 Jun;61(6 Suppl):1360S-1367S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1360S. PMID: 7754988].

Since then, many studies have confirmed the cardio-protective effect recorded by Keys.

[Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease and Protection by the Mediterranean Diet. Francesco Sofi, Alessia Fabbri , and Alessandro Casini. Mediterranean Diet: Dietary Guidelines and Impact on Health and Disease (Nutrition and Health) 1st ed. 2016; Edition by Donato F. Romagnolo (Editor), Ornella I. Selmin (Editor), p.p. 1-345, ISBN 978-3-319-27969-5 (eBook), DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-27969-5, Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London].

- Another study, by the European Atomic Energy Commission (EURATOM) from 1963 to 1965, recorded the quality-quantity of food consumed and compared the dietary patterns of nine regions in Northern Europe and two regions in Southern Europe. Although no absolute differences in fat intake were observed between the North and South regions, the types of fat and the foods contributing to total fat intake were quite different.

- Butter consumption was higher in the Northern regions while olive oil was the main source of fat in the Southern regions. Margarine was not consumed by the Southern regions, while less meat and more cereals, fruits and vegetables were consumed.

- [Nestle M. Mediterranean diets: historical and research overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995; 61 (6 Suppl): 1313S–2].

- After these studies and of course many others that followed, the beneficial effects of the Mediterranean dietary pattern (MDP) in reducing chronic diseases, myocardial and cardiovascular mortality, metabolic syndrome, antioxidant capacity, and event frequency in patients with previous myocardial infarction became widely accepted.

- [Updating the Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: From the Heart to the Earth, Lluis Serra-Majem and Antonia Trichopoulou. Mediterranean Diet: Dietary Guidelines and Impact on Health and Disease (Nutrition and Health) 1st ed. 2016; Edition by Donato F. Romagnolo (Editor), Ornella I. Selmin (Editor), p.p. 1-345, ISBN 978-3-319-27969-5 (eBook), DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-27969-5, Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London].

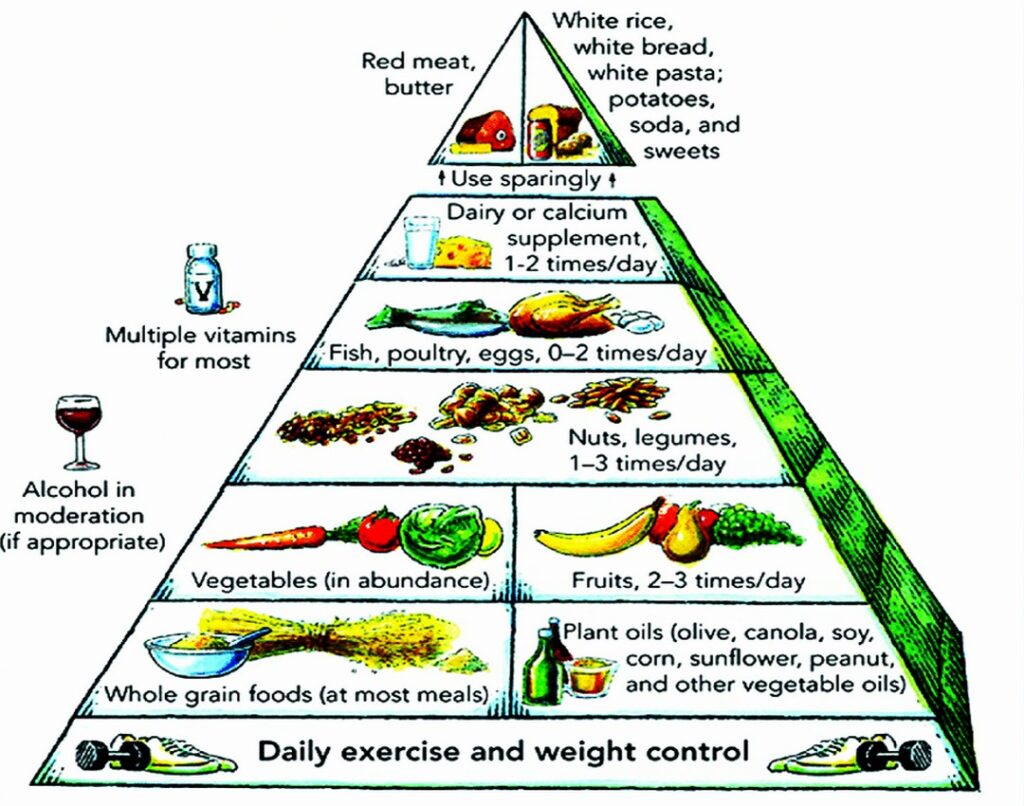

- In 1993, at the first of a series of conferences entitled “Public Health Impacts of Traditional Diets,” a group of experts in nutrition, diet, and health met to review the research on the composition and health effects of the MDP. Modeled after the USDA Food Guide Pyramid, an MDP pyramid was developed, based on the dietary patterns observed in countries around the Mediterranean basin in the early 1960.

- [Willett WC, Sacks F, Trichopoulou A, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid: a cultural model for healthy eating. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995; 61 (6 Suppl): 1402S–6].

- Following the 1993 meeting, the International Congress on the Mediterranean Diet was convened in Barcelona in 1996 and this led to the signing of the “Barcelona Declaration on the Mediterranean Diet”, whose main objective was the preservation of traditional Mediterranean dietary habits and high-quality food production.

- The proceedings of this meeting emphasized the health-eating aspects of the diet and included cultural and historical aspects of nutrition. Since then, the meetings have been held every 2 years and the proceedings have been published in special issues of Public Health Nutrition.

- [Dernini S, Berry EM, Bach-Faig A, Belahsen R, Donini LM, Lairon D, Serra-Majem L, Cannella C. A dietary model constructed by scientists. In Medi Terra: The Mediterranean diet for sustainable regional development, 1st ed. Presses de Sciences Po; 2012. p. 71–88].

- The updated version of the Mediterranean pyramid was released in 2010 and, unlike the previous version, included food quantification by addressing portion sizes and frequency.

- The updated visual representation of the pyramid follows the previous pattern. The base of the pyramid consists of foods that should maintain the diet. Foods that should be consumed in moderate or limited amounts are included at the upper levels. The graphic was accompanied by messages that incorporate lifestyle factors in addition to dietary habits (Fig. 4.2).

- [Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011; 14 (12A): 2274–84] [Fundación Dieta Mediterránea. Mediterranean diet pyramid, http://dietamediterranea.com/dietamed/piramide_INGLES.pdf].

Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011; 14 (12A): 2274–84] – [Fundación Dieta Mediterránea. Mediterranean diet pyramid, http://dietamediterranea.com/dietamed/piramide_INGLES.pdf].

- In 2007, an interstate application was submitted to UNESCO by the governments of Greece, Italy, Morocco and Spain for the recognition of the MDP. Since 16.11.2010, the MDP has been inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, UNESCO. In 2013, it was recognized as an intangible heritage of Italy, Portugal, Spain, Greece, Cyprus, Croatia and Morocco.

- [UNESCO, Decision of the Intergovernmental Committee: 8.COM 8.10, https://ich.unesco.org/en/Decisions/8.COM/8.10].

- The efforts of local organizations and individuals between 2008-2011 to recognize the “Cretan Diet” as cultural heritage were, for various reasons, unsuccessful.

- Although there are many similarities in the foods consumed in Mediterranean countries, the definition of the Mediterranean diet protype as a set of dietary habits and lifestyles varies by region of the Mediterranean basin and by country. Dietary intake may also differ within individual countries, as dietary patterns are influenced by traditions, culture, religion and economy.

- [Simopoulos AP. The Mediterranean diets: what is so special about the diet of Greece? The scientific evidence, J Nutr. 2001; 131 (11 Suppl): 3065s–73s]. – [Essid MY. History of Mediterranean food. In Mediterra: The Mediterranean diet for sustainable regional development, 1st ed. Presses de Sciences Po; 2012. p. 51–69].

- Noah and Truswell explored these similarities and differences by interviewing women who had migrated to Australia from Spain, southern France, Italy, Malta, Croatia, Bosnia, Albania, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco. They grouped dietary patterns into four distinct regions based on dietary habits that are similar between neighboring countries. They identified the patterns of the Western Mediterranean, Adriatic, Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa.

- [Noah A, Truswell AS. There are many Mediterranean diets. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2001; 10(1): 2–9].

- The Eastern Mediterranean group includes Greece, Lebanon, Cyprus, Turkey and Egypt. These countries consume white wheat bread. Bulgur, crushed wheat grains, is consumed exclusively in this group of countries. Dairy consumption is high, including yogurt and cheese. Legumes are frequently consumed. Vegetables, stews and salads are widely consumed, including rice and minced meat. Herbs used include dill, parsley and oregano. Fruit consumption is moderate. Olive oil consumption varies from negligible (Egypt) to high (Greece). Chicken consumption is high with moderate levels of beef and lamb.

- [Noah A, Truswell AS. There are many Mediterranean diets. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2001; 10(1): 2–9]. – [Rivera D, Obón C, Heinrich M, Inocencio C, Verde A, Fajardo J. Gathered Mediterranean food plants—ethnobotanical investigations and historical development. Forum Nutr., 2006; 59: 18–74].

- At the Third Forum on Mediterranean Food Cultures, held in 2005 at the Sapienza University of Rome (The 2005 Rome Call for a Common Action on Food in the Mediterranean), participants agreed on a common definition of the MDP, recalling that the ancient Greek word dieta (diet) meant “balance”, “way of life” and the MDP was defined as a whole lifestyle model with physical activity playing an important role.

- It was emphasized that the uniqueness of the Mediterranean dietary pattern is not only related to a list of foods (some traditional) but also to their sustainability (mainly fresh, seasonal and locally grown), their preparation, the way and context in which they are consumed.

- [Dernini Sandro, 2006. Towards the progress of the Mediterranean διατροφικές κουλτούρες. Δημόσια Υγεία Nutr 9, 103-104. Public Health Nutrition, 9, 103-4. 10.1079/PHN2005930].

- The messages of the Cretan Mediterranean diet:

- It has evolved as a way of life.

- It is aimed at healthy adults and should be adapted to the special needs of children, pregnant women and other needs.

- It places plant-based foods at the base. These provide essential nutrients and protective substances that contribute to general well-being, maintaining a balance in appetite, digestion and metabolism.

- Modified from: [Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011; 14 (12A): 2274–84].

- Every day: (1) Grains. One or two servings per meal in the form of bread, pasta, rice, couscous, and more; preferably whole grains.

- (2) Vegetables. For lunch and dinner, two servings per meal, at least one of the servings should be raw. Choose a variety of colors and textures for better antioxidant protection. (3) Fruit. One or two servings per meal.

- Stay well hydrated with water and herbal teas, reduce the salt content of food.

- Prefer yogurt. Olive oil is the main source of fat. Include olives, nuts, and seeds. Moderate wine consumption, only if compatible, with the meal.

- Modified from: [Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011; 14 (12A): 2274–84].

- Weekly: Fish (two or more servings), white meat (two servings) and eggs as good sources of animal protein. Fish and shellfish as good sources of healthy fats.

- Consume legumes (more than two servings/week) and cereals as healthy sources of protein and fat.

- Potatoes (two-three servings/week), as part of traditional meat and fish recipes.

- Consume small amounts of red meat (less than two servings per week).

- Modified from: [Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011; 14 (12A): 2274–84].

- Rarely: Sweets, candies, cakes, soft drinks.

- Continuously: Emphasis on lifestyle elements, such as,

- “Everything is fine in moderation”,

- socialization through serving food,

- cooking at mild temperatures,

- seasonality of food,

- traditional and local food products,

- physical activity,

- adequate rest.

- Modified from: [Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011; 14 (12A): 2274–84].

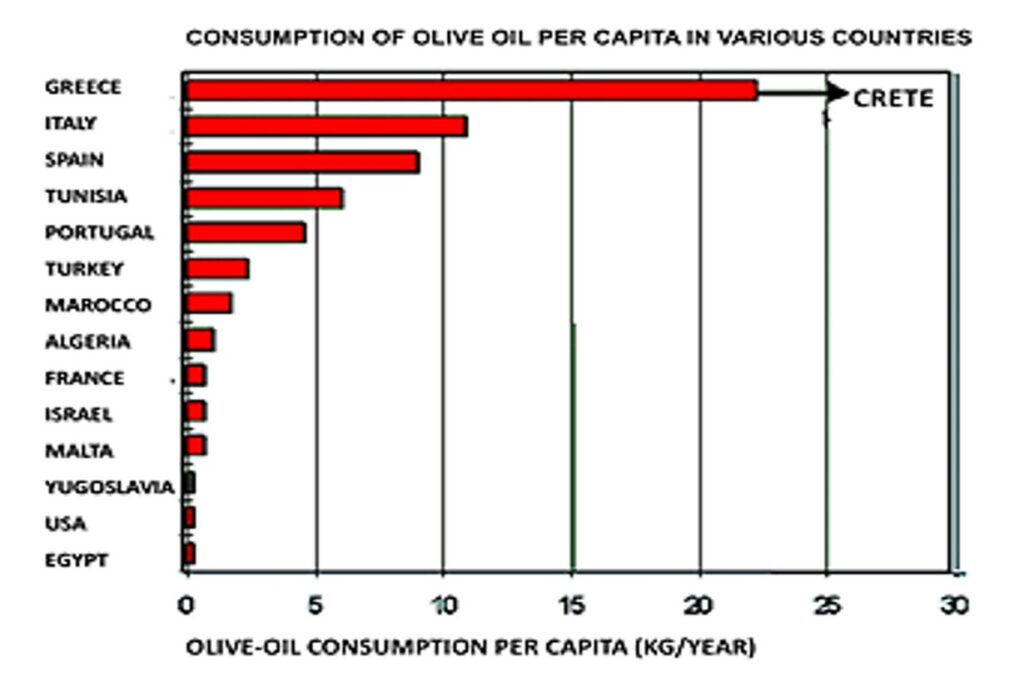

According to the Association of Olive Growing Municipalities of Crete (SEDIK): [https://www.sedik.gr/neo/el/ελια-και-λαδι/καταναλωση].

- Many of the characteristic components of the Mediterranean diet have positive health effects, because they are functional foods.

- Vegetables, fruits and nuts are rich in phenols, flavonoids, isoflavonoids, phytosterols.

- Polyunsaturated fatty acids found in fish regulate hemostatic factors, protect against cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension, etc.

- Olive oil is known for its high levels of monounsaturated fatty acids and is a good source of phytochemicals, such as polyphenolic compounds, squalene and α-tocopherol.

- [Ortega R. Importance of functional foods in the Mediterranean diet. Public Health Nutr. 2006 Dec; 9(8A): 1136-40. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007668530. PMID: 17378953].

- The concept of MDP has undergone a progressive evolution over the past 60 years, from a healthy dietary pattern to a sustainable dietary pattern, in which nutrition, food, cultures, people, environment and sustainability interact in a new model of sustainable nutrition.

- Adherence to MDP is declining due to multifactorial influences – changes in lifestyle, food globalization, economic and socio-cultural factors. The challenge today is to reverse these trends.

- [Dernini S, Berry EM. Mediterranean Diet: From a Healthy Diet to a Sustainable Dietary Pattern. Front Nutr. 2015 May 7;2:15. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2015.00015. PMID: 26284249; PMCID: PMC4518218].

- The rural space in Greece is undergoing a significant transformation. Over the last four decades, the traditional urban-rural dichotomy has given way to complex spatial patterns, which are undergoing a process of continuous change.

- Rural development no longer depends exclusively on the agricultural sector, but also on the relations with cities and the presence of a variety of economic activities in rural areas, such as tourism.

- General rural and rural development policies have an impact on rural patterns and living standards.

- [Iliopoulou, Polixeni & Stratakis, Panagiotis & Tsatsaris, Andreas. (2008). Transformation of Rural Patterns in Greece in a European Regional Development Perspective (The Case of Crete). In book: Regional analysis and policy: the Greek experiencePublisher: Physica – Verlag Editors: Harry Coccossis, Yannis Psycharis].

- “Rediscovering” the tradition and social capital of rural society: Local social and economic actors, taking advantage of the framework of the social economy, can produce goods such as food and using local social relations to form a multifunctional whole that is locally shaped and supports life in the countryside.

- [Spyridakis, Manos & Dima, Fani. (2017). Reinventing traditions: Socially produced goods in Eastern Crete during economic crisis. Journal of Rural Studies. 53. 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.04.007].

- A sense of belonging and community needs to be cultivated. Social capital builds social contact and interaction, as well as the creation of networks that enable a shared way of life.

- However, social capital also means collective trust, implied in almost any concept of group or community. This collective trust helps people to develop as a group and change their way of life.

- More approaches are needed from a socio-cultural perspective, taking into account the importance of those perspectives that are built by the interaction of people as members of societies and, therefore, create social capital.

- [Medina F-X, Sole-Sedeno JM. Social Sustainability, Social Capital, Health, and the Building of Cultural Capital around the Mediterranean Diet. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054664].

Yubero-Serrano, E.M., Gutierrez-Mariscal, F.M., Perez-Martinez, P., Lopez-Miranda, J. (2020). The Mediterranean Diet. In: Uribarri, J., Vassalotti, J. (eds) Nutrition, Fitness, and Mindfulness. Nutrition and Health. Humana, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30892-6_2